How to Scale Startup Energy

| 36 min read

In any group, whether it’s 10 people or 10,000, much of the energy ends up being wasted rather than directed towards a common goal. The amount of wasted energy tends to increase as groups scale, leading large organizations to trend toward ineffectiveness over time.

However, in those rare moments when a group’s energy is fully aligned and channeled towards a shared objective, extraordinary things become possible. This is why 10 person startups can out-compete 10,000 person organizations: it’s entirely possible that the 10 person company can direct more energy towards building a great product or new technology than the 10,000 person organization.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Part One: The Insight

Imagine you’re part of a small, tight-knit team working on a project that everyone is passionate about. Ideas are flowing, decisions are made quickly, and progress is happening at a pace that seems almost miraculous. The energy is electric, and everyone feels a sense of purpose and fulfillment in their work.

The project is a huge success, and the team grows rapidly to meet the demands of scale. But as the team grows, things start to change. Meetings drag on without clear outcomes, decisions get bogged down in politics and bureaucracy, and the once-electric energy dissipates into frustration and disengagement. The very growth that was a result of your success now seems to be the thing holding you back.

As cofounder of Tradesy, I lived this paradox firsthand as we grew from a scrappy startup to a company of hundreds. I watched our once-nimble team get bogged down in the very processes and structures we had put in place to enable our growth.

Eventually progress ground to a halt, growth stalled, work stopped being fun, and we entered a period of crisis. I became convinced that the only way through was to tap into the energy and effectiveness we had effortlessly cultivated as a small team huddled around the kitchen table in my cofounder’s apartment.

Organizational Entropy

Over the next few years, I became obsessed with understanding what had caused our once-thriving startup culture to break down as we scaled. I went deep into the field of group dynamics, seeking to uncover the root causes of our dysfunction. What I discovered was that the forces that drain a group’s energy and lead to ineffectiveness are not random or inevitable, but rather the predictable result of unconscious patterns that emerge when people come together to work towards a shared goal.

When left unchecked, these unconscious patterns ossify and crystalize into the common problems that are so familiar in large organizations. Communication breaks down, decision-making slows to a crawl, and politics and bureaucracy choke the life and creativity out of the work. The larger the organization, the more of its productive energy is dissipated into these unproductive activities, until it feels impossible to accomplish anything at all. I call this phenomenon organizational entropy.

The Four Noble Truths of Group Flow

In order to prevent dysfunction, we need to focus on the causes of organizational entropy, rather than it’s manifestations. It is only when we properly address and integrate these energy-dissipating patterns that we are able to cultivate and sustain states of high performance at scale.

This is the core insight at the heart of Group Flow, and it can be articulated as follows:

- Dysfunction Groups trend towards ineffectiveness as they grow because more and more of their energy is lost to unproductive activities (organizational entropy), rather than being directed towards a common goal.

- The Cause of Dysfunction Organizational Entropy is caused by specific patterns of unconscious behavior that dissipate the group’s energy.

- The End of Dysfunction By bringing awareness to these dynamics and skillfully working with them, the tendency towards entropy can be counteracted. Dysfunction is not a necessary byproduct of scale, but rather the result of unconscious patterns going unaddressed.

- The Path to Flow When the causes of entropy are understood and managed, states of flow emerge naturally. In these states of group flow, the full potential of the collective is unleashed. Energy is channeled effectively towards a common goal, and remarkable things emerge.

Armed with this insight, we set about rebuilding Tradesy from the ground up, and we saw a resurgence of innovation and growth. New features and initiatives that previously would have gotten stuck in the quagmire of indecision and process began to take shape and come to life in weeks rather than months or years. We launched bold experiments, entered new markets, and refocused on our customers, all with an agility and speed that belied our size.

Even more importantly, we created a thriving culture where people felt deeply engaged, connected, and fulfilled in their work. The old silos and turf wars gave way to a spirit of collaboration and shared purpose. People brought their whole selves to work, knowing that their unique perspectives and passions were not just welcome, but essential to our collective success. The energy and excitement were palpable–it felt like we had bottled the magic of our startup days.

The results spoke for themselves. Over the next few years we reached new milestones in growth, profitability, and efficiency. Our team was firing on all cylinders, and the business thrived as a result. With this newfound level of performance we were able to not only weather the storm we had faced, but emerge stronger on the other side, ultimately reaching a successful exit.

If you’re thinking “sure, this sounds great, but you haven’t seen MY company,” I get it. I’ve been there. It was only after repeatedly hitting the wall at Tradesy that I became convinced that a different way must be possible, and it took years of experimentation and learning before the solution came into focus.

Here’s the thing: once you start to see the patterns that lead to dysfunction, you can’t unsee them. And once you experience the magic of a group truly in flow, you won’t want to settle for anything less.

In the following sections, we’ll unpack key principles and practices to cultivate and sustain states of group flow in teams of any size.

First, we’ll map out the tension between productive flow states and the forces that pull groups towards dysfunction and ineffectiveness. With this framework in place, we’ll outline practices for continually re-aligning a group’s energy by detecting unproductive patterns and redirecting that potential towards the group’s goals. You’ll walk away with a comprehensive toolkit for channeling group energy that works at any scale.

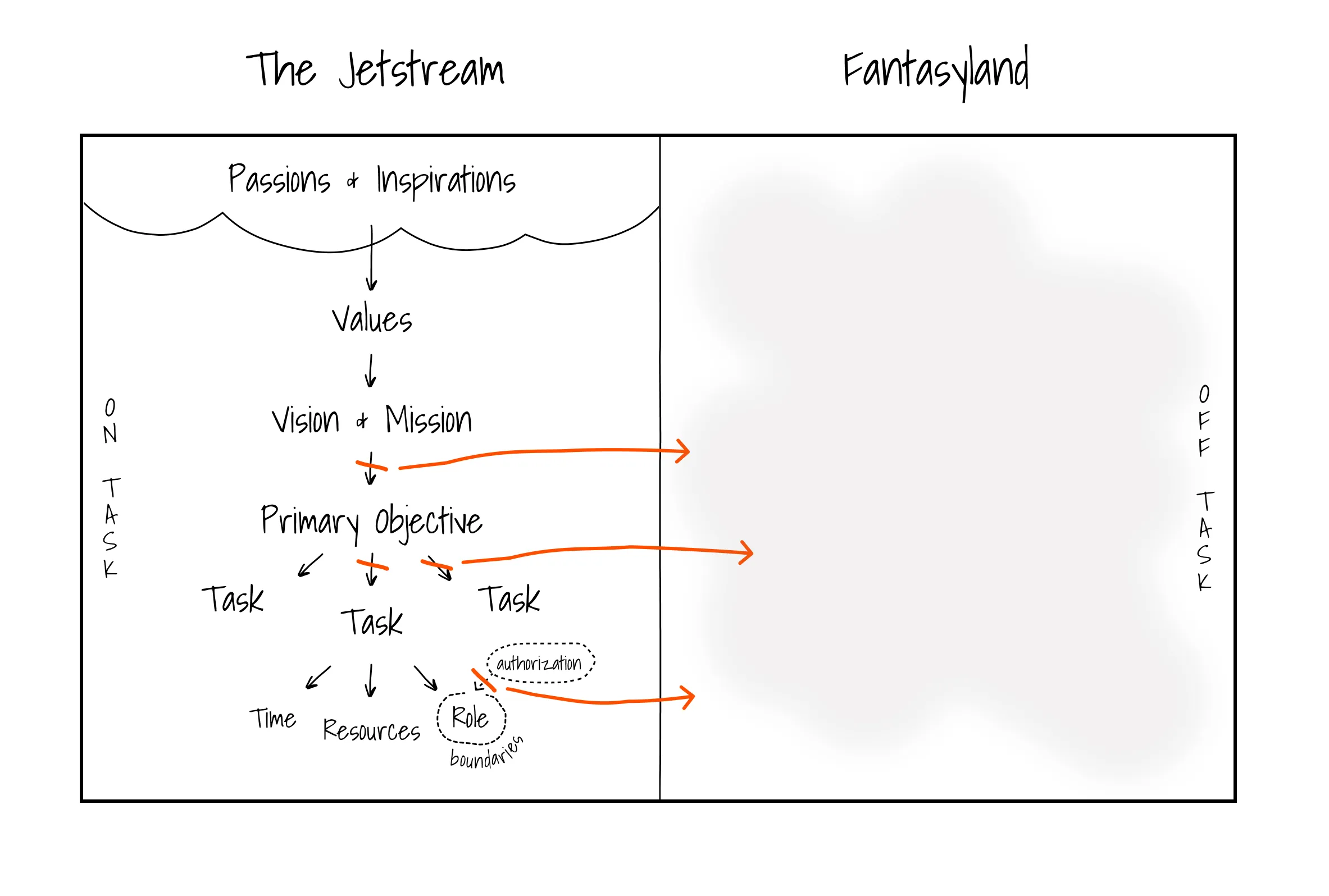

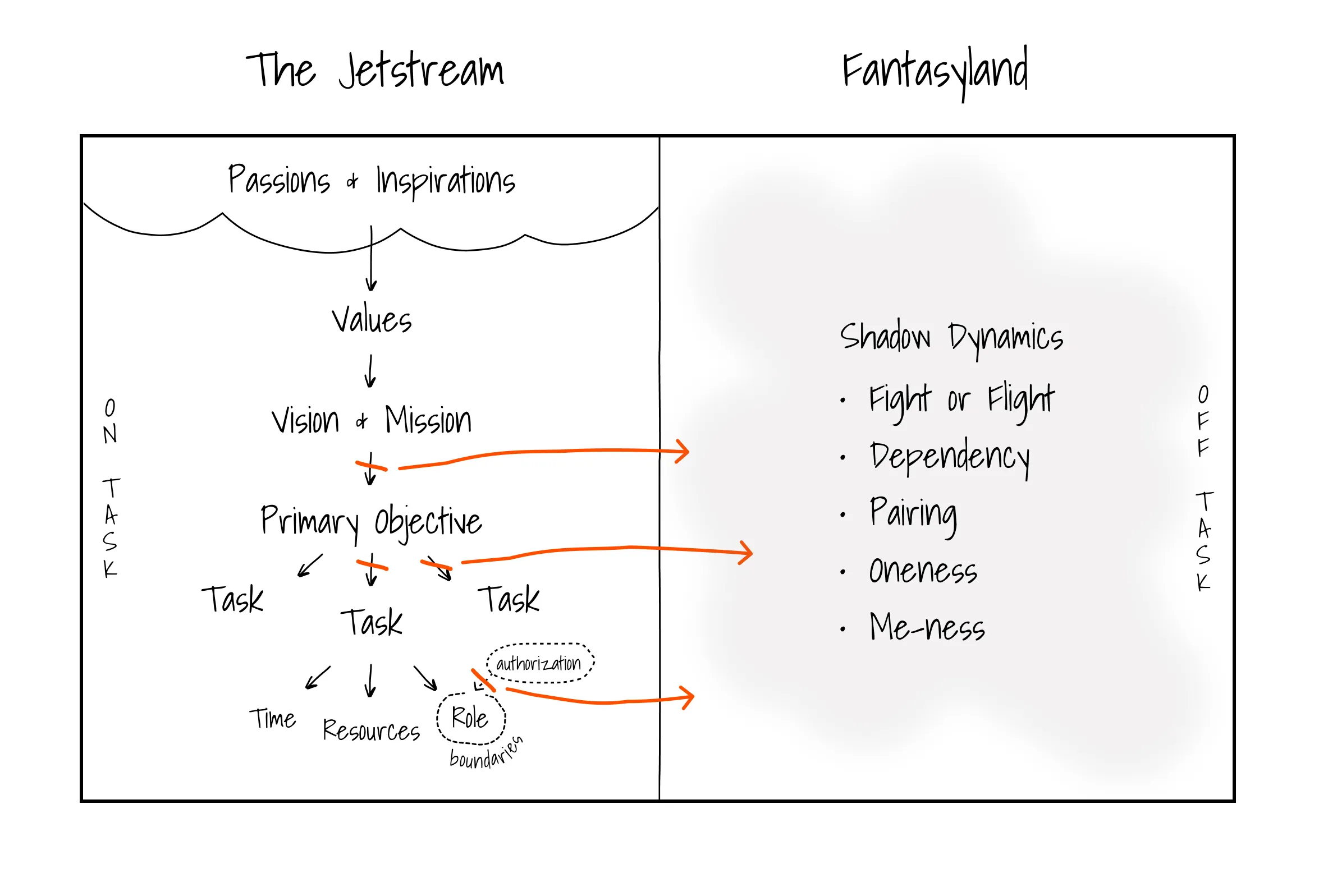

Part Two: The Jetstream

Tremendous energy is available when you orient the work of a group in such a way that every task is maximally impactful in advancing towards a common goal. Important work is prioritized, and progress is accelerated towards the destination. People are energized, motivated, and happy. It’s fun. This state of flow is the Jetstream, and it’s where we all aspire to be when working in groups.

The Primary Objective

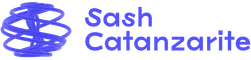

Groups come together to accomplish a goal that is too large for any one individual to achieve alone. We call this common goal the group’s primary objective.

In order to be effective, the primary objective needs to be specific enough to provide clear direction, ambitious enough to inspire and challenge the group, and time-bound in order to establish an expectation of pace. In an organization using OKRs, the primary objective would be the company level OKR. While the exact form of the primary objective may vary depending on the organization’s goal-setting methodology, the key principles remain constant.

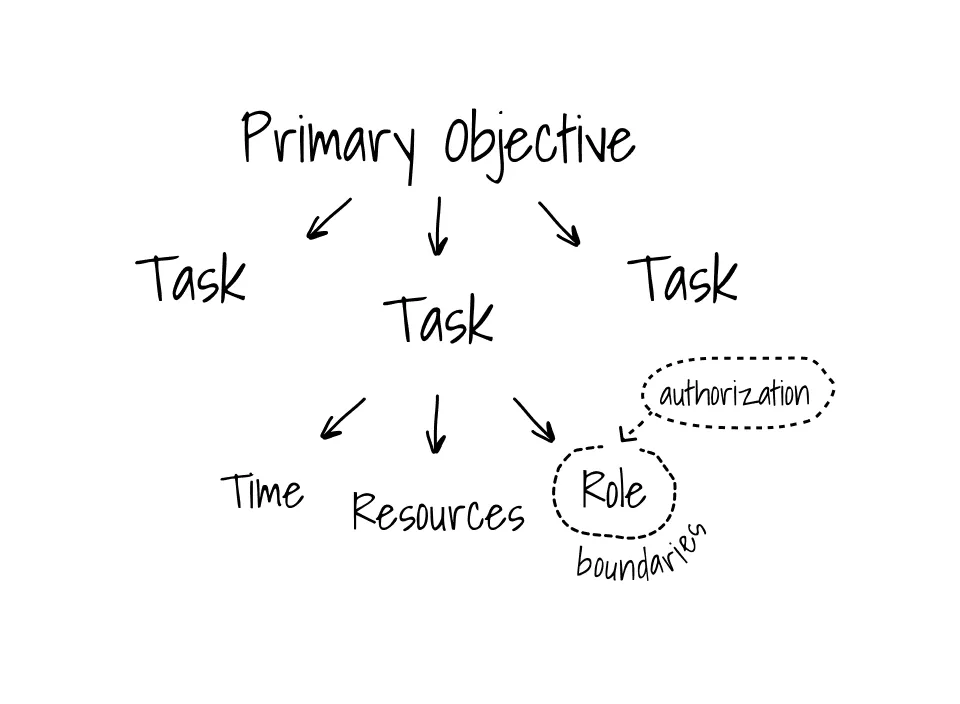

By definition, the primary objective is too large for any one individual, and it therefore needs to be broken down into discrete units of work, or tasks that can be taken on by individuals.

Task Constellations

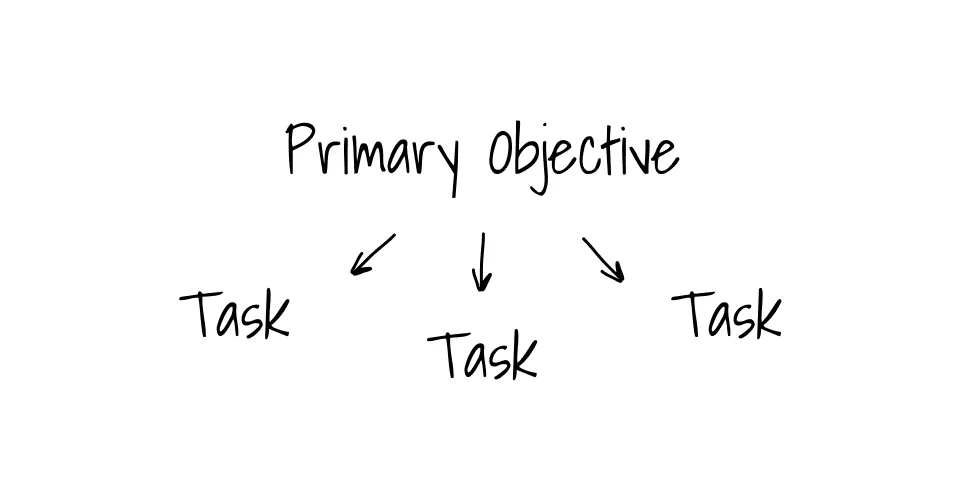

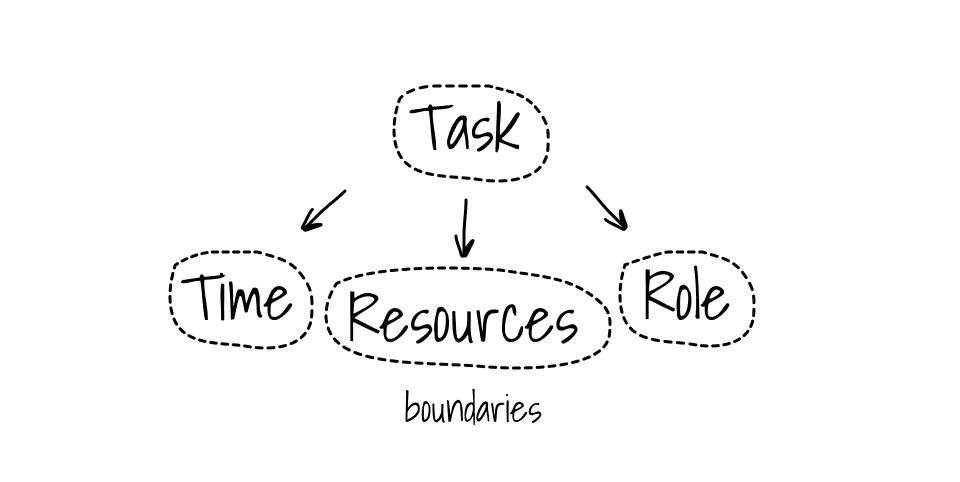

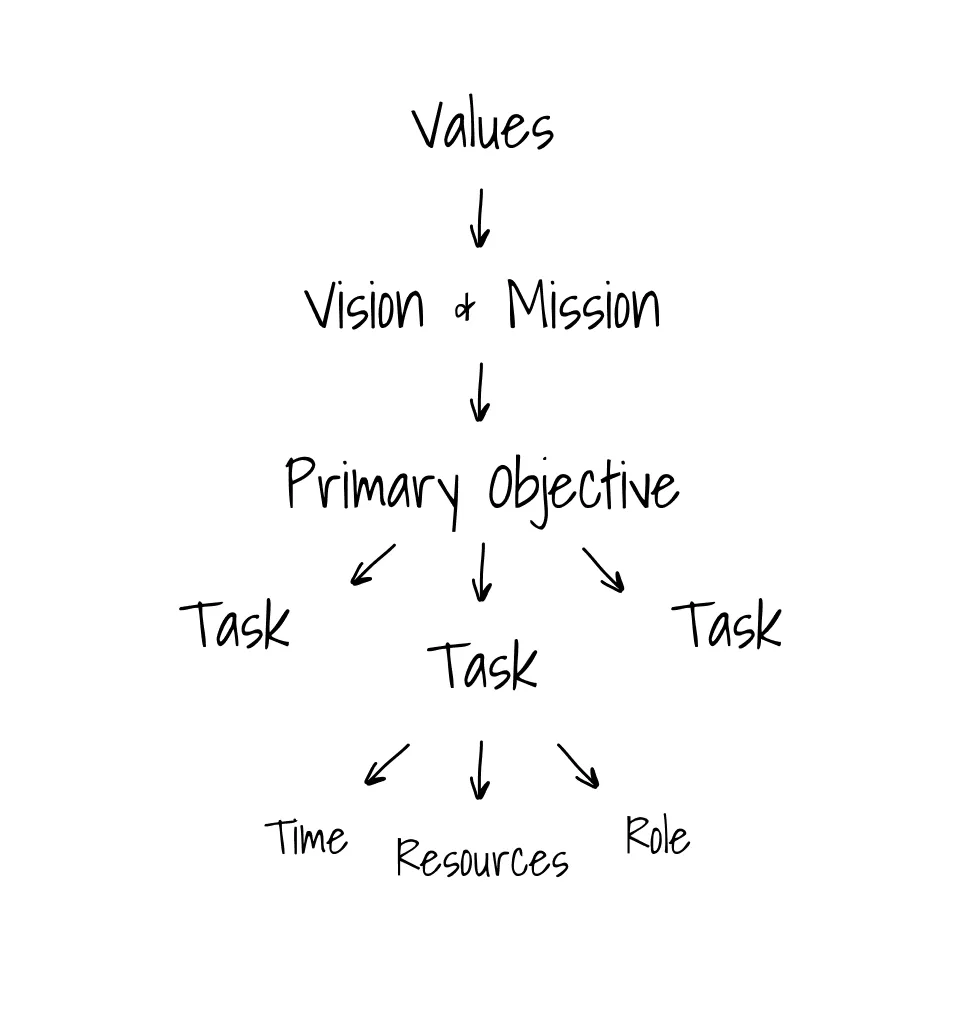

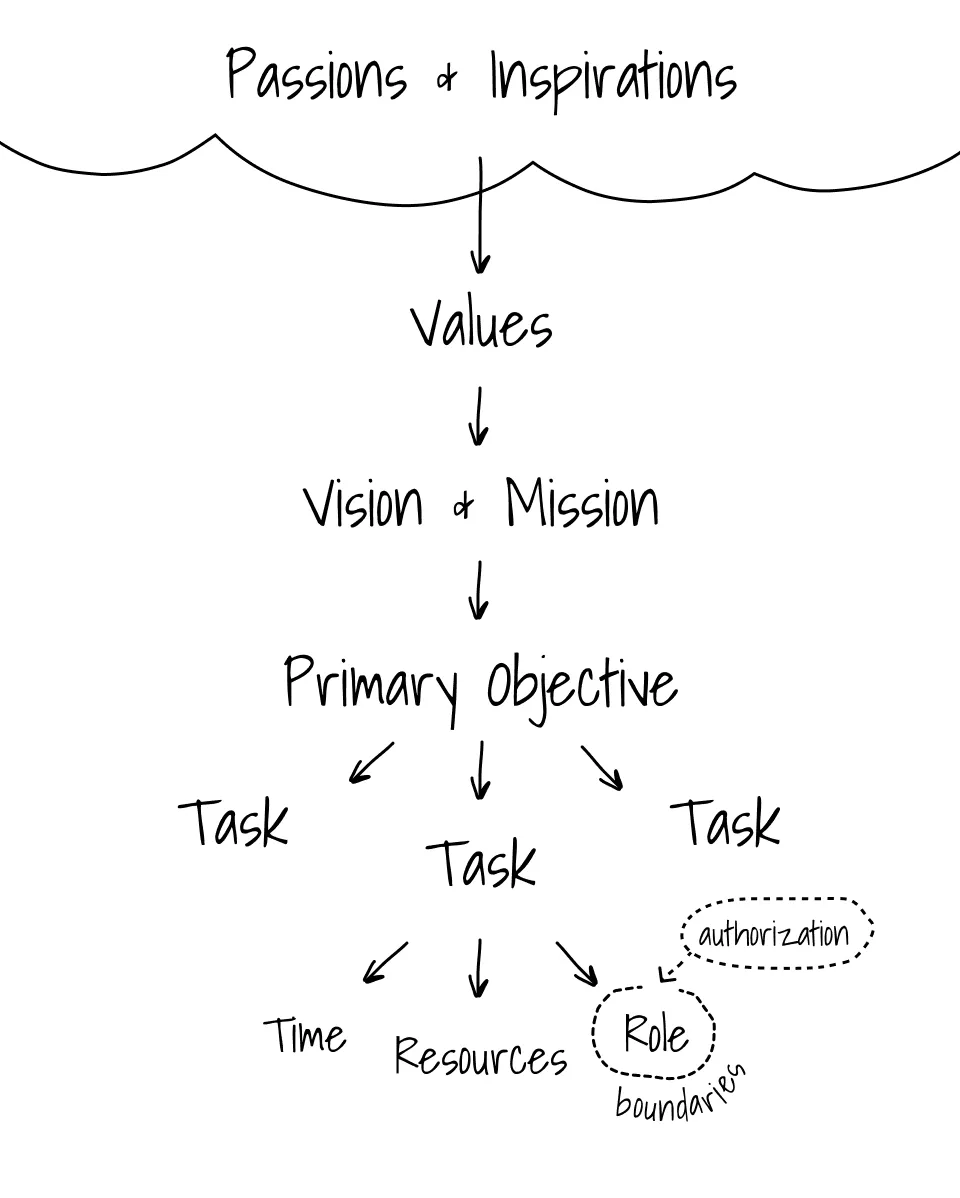

In order complete a task, individuals need 4 things:

- Task - a clearly defined unit of work that aligns with the primary objective.

- Time - the ability to manage their time such that they’re able to perform the work required to complete the Task.

- Resources - external resources that may be required to complete the work. This can be anything needed to get the job done — money, computers, other people, robots, manufacturing capacity etc.

- Role - a clearly defined role that articulates what the individual is responsible for delivering.

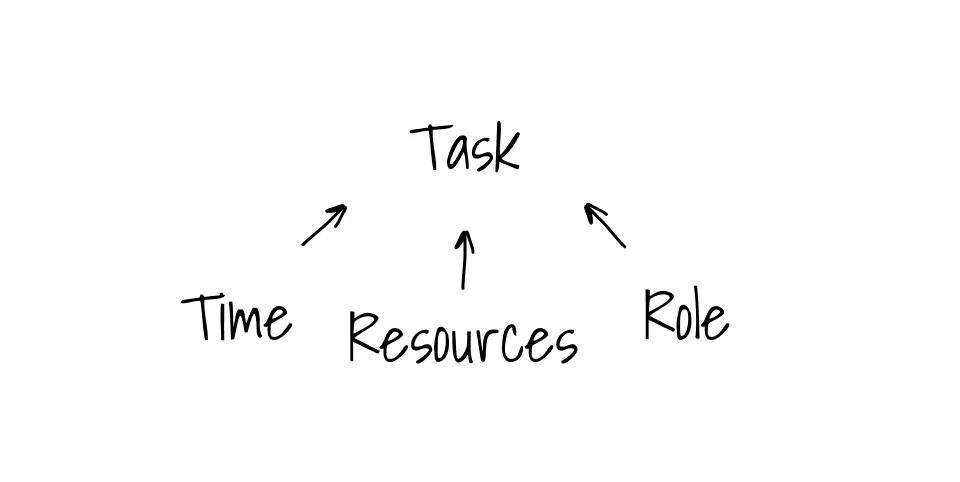

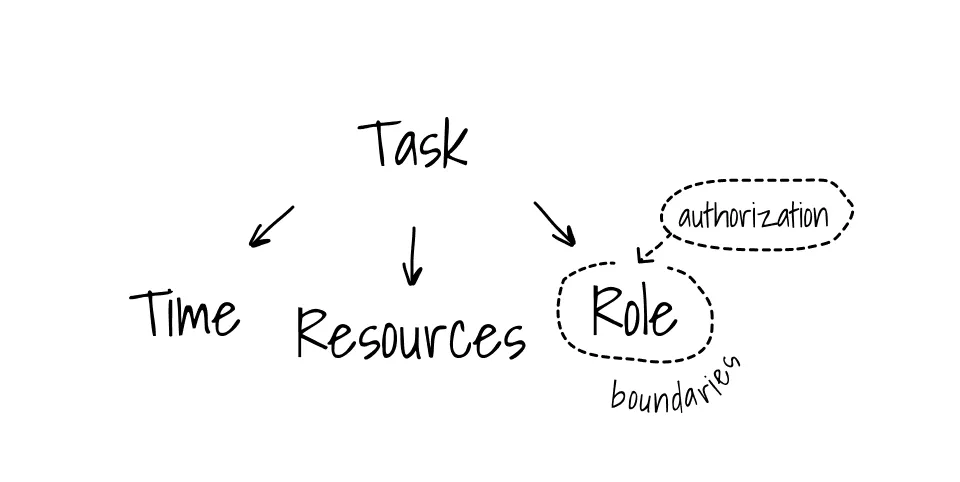

The process by which the group grants an individual ownership over their time, task, resources, and role is called authorization. When an individual is fully authorized, they have a clear sense of their place within the group and the legitimacy of their contribution. They feel empowered to make decisions, take action, and own their work without constantly seeking permission or validation from others.

It’s important to note that while in traditional organizations authorization often flows from the top down, it can actually flow from four different directions – from above, below, laterally from peers, or from within individuals themselves.

Surrounding each of the task components is a boundary. Boundaries are crucial for effective group functioning on multiple levels. At a practical level, clear boundaries prevent individuals from stepping on each other’s toes by delineating who is responsible for what, what Resources are allocated to each task, and how time and effort should be spent.

But boundaries also serve deeper psychological and interpersonal functions. Well-defined boundaries contribute to a sense of psychological safety, allowing individuals to take risks, share ideas, and engage in productive conflict without fear of overstepping or being undermined.

Boundaries and authorization are also deeply intertwined. Clear, well-defined boundaries provide the framework for authorization. When an individual understands the boundaries around what they are responsible for, what resources they have, and how their work fits into the bigger picture, they are more likely to feel fully authorized to own their tasks and make decisions within their domain.

Pulling it all together, we can represent time, task, resources, and role as a discrete structure with corresponding boundaries and a flow of authorization.

This structure is a complete representation of an individual’s contribution to the group’s primary objective at any moment, and as such, it is actually useful to look at groups as constellations of time, task, resources, and roles rather than as collections of individuals. We’ll revisit this idea that individuals are less solid than they seem later on.

The Flight Plan

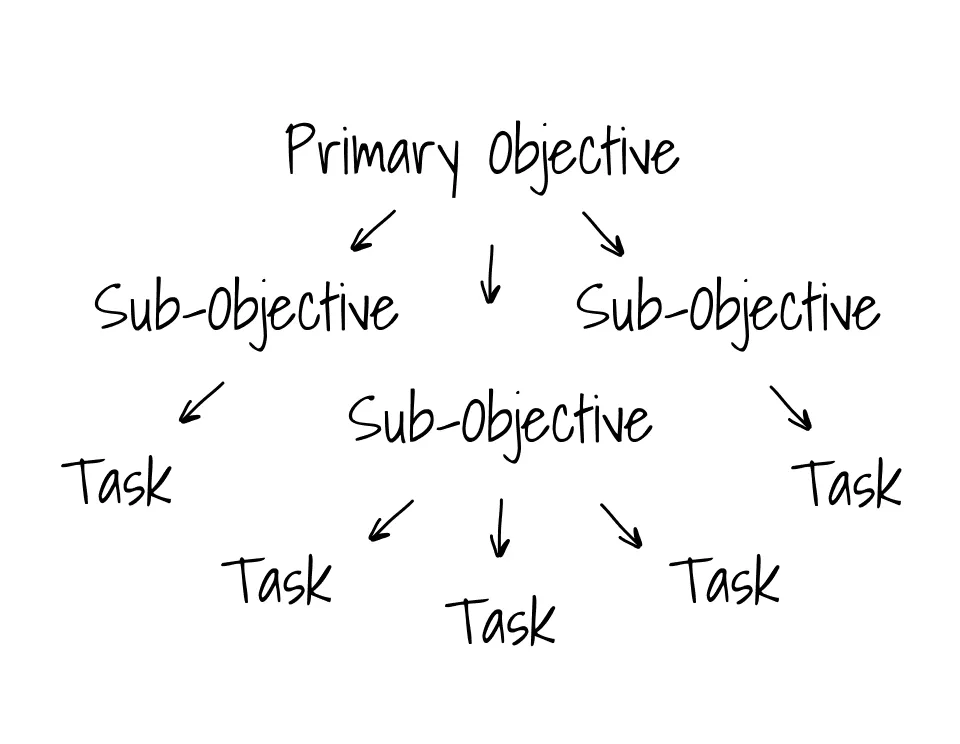

When you put all the group’s task structures together, you get a simple hierarchical representation of work being done in service of the primary objective.

We’re going to call this the group’s flight plan. A high-functioning flight plan is characterized by clarity, alignment, and prioritization among tasks in relation to the primary objective.

Depending on the size and structure of the group, the primary objective may need to be broken down into sub-objectives owned by smaller groups or teams before it can be broken down into tasks for individuals. In a large or complex organization the flightpPlan takes on a fractal structure, but the fundamental principles are the same.

Energy source of the Jetstream

We now have the beginnings of a map of The Jetstream, but we’re not quite done. While the primary objective is the common goal that the group is working towards over a specific time period, it operates within the context of higher level goals and principles. The group’s mission, vision, and values can be thought of as the energy source that sustains the group as the primary objective changes over time.

I define mission, vision, and values as follows:

- Mission - the group’s long term goal. A great mission is ambitious enough that it will take many years to accomplish, while being believable enough to be an inspiring call to action.

- Vision - a shared understanding of how the world will look if the group accomplishes the Mission.

- Values - a set of implicit or explicit principles that define how the group will behave while working together.

At the highest level, the energy of the group comes from the individuals within it. This means that in order to access the energy available within the group, the flight plan must also align with the larger context of who the individuals are and where they’re going in life.

Each individual has constellation of things that make them uniquely who they are. We’ll call this the individual’s passions and inspirations. This tends to be a series of 3-5 things that come together to create a moment of “Ah, this is it. This is why I’m here on this planet.”

My passions and inspirations are: working on hard problems, having meaningful relationships with a group of people, doing something creative, and being in nature. It’s rare for all four of my passions and inspirations to come together in a single moment, but when they do that’s pure magic for me. Hence my deep appreciation for Burning Man, and why having company retreats at a summer camp in the redwoods was a peak experience for me.

Three out of four of my passions and inspirations coming together in one moment is more common, and still creates a deep resonance of meaningful experience. In these moments I not only experience tremendous existential juice, but crucially also tap into a deep and profound internal source of energy.

So in in order for an individual to access their deepest and most profound source energy when working in a group, the tasks they own need to be connected to their passions and inspirations by a clear flight plan.

This is not always straightforward, so drawing these lines is a key function of managers. For instance a junior engineer may have passions and inspirations that include solving complex problems and creating something new. However, as a junior engineer their job may look a lot more like re-writing other peoples shitty code than solving novel and interesting problems.

As a manger, you may need to explain that if they spend a few months fixing bugs and learning the codebase, they’ll graduate to writing small enhancements, then whole features, and in several years they’ll be ready to architect new systems. In this way, their current tasks can be connected to their passions and inspirations even if they don’t directly fulfill them today.

When your flight plan enables you to draw a straight line from the tasks that individuals are working on every day to the primary objective of the group to the vision and mission and values of the organization, all while tapping into the energetic source of each individual’s passions and inspirations, you have a recipe for happy, motivated individuals and rapid progress towards a common goal.

This is The Jetstream–that optimal state of flow in which the group is fully aligned and moving forward with clarity, purpose, and tremendous momentum. It’s a state of high performance, high engagement, and high fulfillment.

But as desirable as The Jetstream is, we know it’s not that common, especially in large groups. In the next section, we’ll explore the forces that pull groups out of alignment and towards entropy and inefficiency.

Part Three: Fantasyland

The Jetstream is the zone of clarity, alignment, and ease facilitated by a high quality plan of action that enables the group to channel energy effectively towards their primary objective. We all want to travel in The Jetstream, but anyone who’s worked in a group knows that it isn’t the default mode. What’s going on?

What inevitably happens in any group, is that small errors creep into the plan, or reality reveals itself to be different from our assumptions in important ways. These breakdowns cause individuals to fall out of alignment with the group’s objectives and slip into a zone governed by unconscious modes of human behavior.

We call this this territory Fantasyland–a realm where progress stalls, confusion reigns, and the group’s potential is left unrealized. In Fantasyland, individuals are no longer oriented towards the group’s primary objective, but are instead pushed around by powerful unconscious forces. It’s as if the group’s energy is being siphoned off, dissipating into inefficient or unproductive channels. This is the essence of organizational entropy.

Pulled Off Task

Breakdowns can happen at any level of our structure. One very common breakdown is a conflict in priorities. Two individuals at the same level in an organization have tasks that compete for time or resources. Unable to resolve this conflict, one or both fall out of alignment with the plan of action. We’ll call this state off task.

Another common issue is a breakdown of authorization. For example, a manager may lose confidence that an individual on their team is capable of doing the job. Perhaps they take the work product and re-do it, perhaps they tear it apart publicly. Either implicitly or explicitly, they erode the authorization of the individual to own time, task, resources, and role. What happens? The individual falls off task.

A less common example might be a breakdown between mission or values and task. In 2018 a group of engineers at Google who were working on a secrete ai project found out that the software they were building was intended to be used in drone strikes. These were engineers who signed up for Google’s mission to organize the worlds information, with a core cultural value of “don’t be evil.” What happened? A wave of protests and resignations. Through the Group Flow lens, a bunch of people were pulled off task, out of The Jetstream and into Fantasyland.

Shadow Dynamics

When individuals fall out of alignment with the group’s objectives, they come under the influence of unconscious, default modes of human behavior that we call Shadow Dynamics. These dynamics serve as psychological defense mechanisms in the face of uncertainty or stress, but they come at the cost of being disconnected from reality.

Shadow Dynamics provide fantasy solutions to unpleasant emotions that divert energy from the primary objective, leading to organizational entropy and ineffectiveness.

There are five Shadow Dynamics:

- Dependency: Individuals abdicate personal responsibility and autonomy, deferring to external authority figures for direction, protection, and decision-making.

- Fight or Flight: A state of heightened vigilance in which everything is perceived as a threat, triggering aggressive responses to eliminate dangers or avoidant behavior to escape them.

- Pairing: Individuals become preoccupied with intense combative or erotic energy between two group members. The rest of the group experiences this passion vicariously as they hang on the pair’s every interaction.

- Oneness: A preoccupation with maintaining harmony, unity, and avoiding conflict within the group, even when necessary to make decisions and get work done. Individuals may suppress their differences and engage in groupthink to preserve a fantasy sense of unity.

- Me-ness: Individuals prioritize personal interests, desires, and ambitions over the collective needs and goals of the group. They may struggle to form genuine bonds with others that are necessary to transmit and receive authorization.

Shadow Goals

When a group falls under the influence of Shadow Dynamics, they begin to operate as if their goal were something other than the primary objective. These shadow goals provide a sense of purpose and direction for those under their influence, but lead the group towards entropy and ineffectiveness by diverting energy away from the primary objective.

The shadow goals for each Shadow Dynamic are:

- Dependency: Obtain guidance and protection from an idealized leader or authority figure.

- Fight or Flight: Ensure the survival of the group against perceived threats or dangers.

- Pairing: Displace the group’s anxieties and avoid the primary objective by investing hope in the pair’s interaction to magically resolve the group’s challenges.

- Oneness: Merge into an undifferentiated, conflict-free state of harmony, unity, and shared consciousness.

- Me-ness: Fulfill individual needs, desires, and ambitions.

In each case, the group is operating based on a fantasy narrative that is disconnected from reality and the primary objective. This disconnect is what makes Fantasyland so insidious - it feels real and compelling to those under its influence, but it ultimately leads the group astray.

Valencies

We can think of Shadow Dynamics as ever-present entropic currents within a group, waiting for opportunities to pull people’s energy away from the primary objective. Each individual tends to have a default Shadow Dynamic, or valency that they are most susceptible to when experiencing stress or disconnection from the group’s goals.

My own default valency is a form of Me-ness that manifests as procrastination and going down unproductive rabbit holes. For instance, if my objective is to write an introduction to Group Flow but the tasks are not clearly defined or there are no boundaries around my time, I may find myself researching new note-taking applications rather than writing. This provides an illusion of productivity while allowing me to unconsciously avoid the actual difficult work at hand.

Certain situations and circumstances also have characteristic Shadow Dynamics.

Conflicts of prioritization commonly result in Dependency, where individuals turn towards a manager to “just tell me what to do.” Alternatively, lack of clear priorities may lead to politics, a form of Me-ness, with individuals jockeying to promote their personal priorities at the expense of the group’s interests.

Breakdowns in the flow of authorization tend to prompt other predictable Shadow Dynamics. When individuals have their authorization undermined or boundaries violated, they often default to the Dependency dynamic, deferring to others they perceive as more empowered to make decisions. Breakdowns in authorization can also trigger Me-ness dynamics of defensiveness and looking out for one’s own interests. In more extreme cases, Fight or Flight dynamics may emerge if the individual views the breakdown as an existential threat to their standing in the group.

Lack of clear boundaries around who is responsible for what can spark power struggles animated by Me-ness. If responsibilities for tasks seem overly distributed with no clear boundaries around ownership, individuals may regress into Dependency, awaiting directions rather than proactively problem-solving.

Often, individual Valencies interact and become entangled with situational ones, adding additional layers of complexity. A person’s default Me-ness tendencies may be exacerbated by ambiguities around roles and responsibilities. An individual’s propensity towards Dependency is more likely to be triggered if their manager has an authoritarian style. The seeds of Fight or Flight can be sown by a particular set of environmental stressors combined with pre-existing insecurities.

Maintaining the cohesive, aligned flow state of The Jetstream requires meticulous, ongoing attunement to dynamics within oneself and within the group as a whole. Navigating this landscape is perhaps the greatest challenge in realizing a group’s full creative potential. We’ll explore how to do it in the next few sections.

Part Four: The Map

Now that we’ve explored both The Jetstream and Fantasyland, we have a map of how energy and consciousness flow through groups.

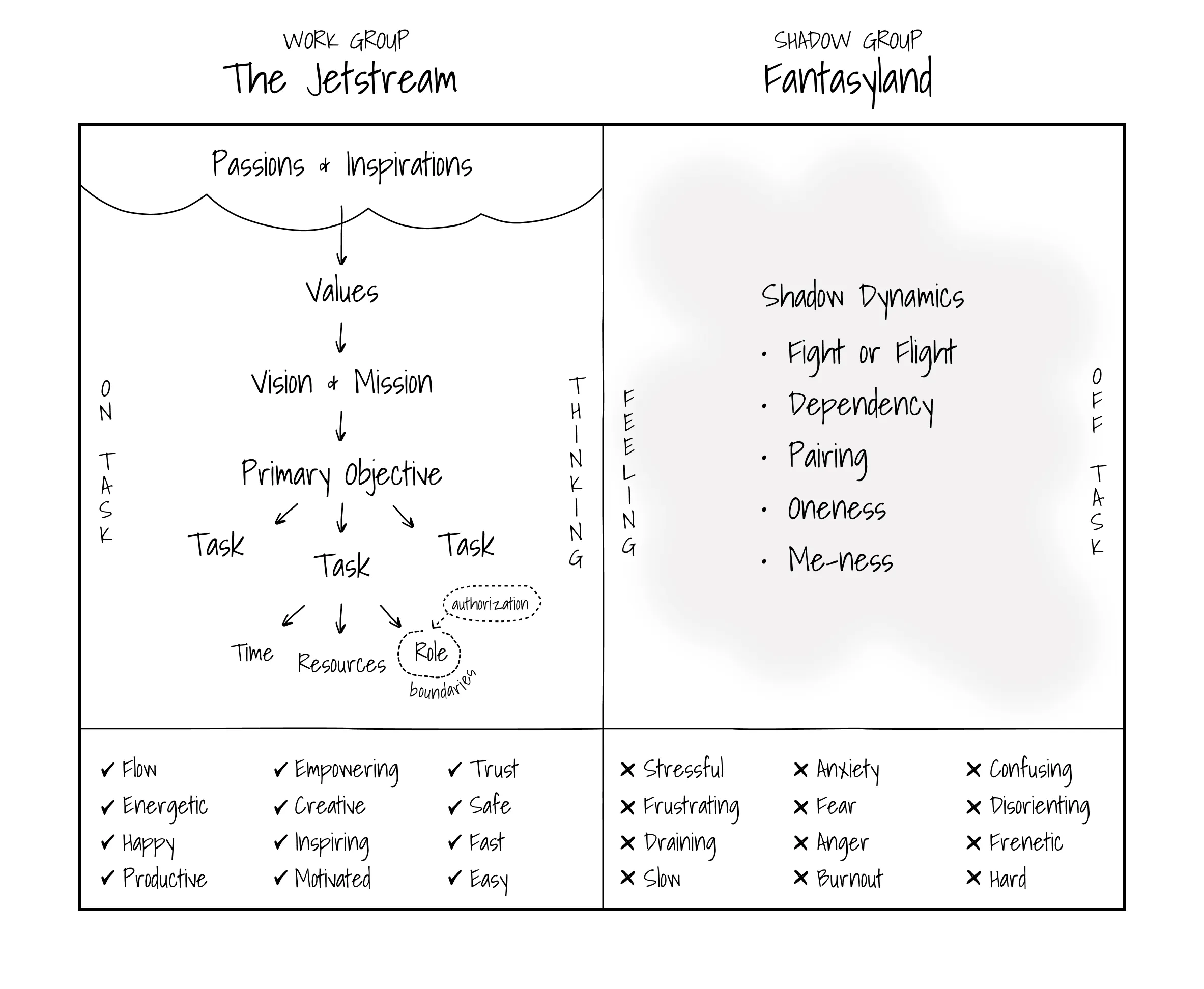

The Jetstream represents that optimal state of flow where a group is fully aligned and moving towards its primary objective with clarity, purpose, and speed. In the Jetstream, the group’s flight plan is clear and compelling at every level:

- The group’s mission and vision provide a powerful “why” that inspires and orients everyone’s efforts.

- The primary objective translates that high-level direction into a specific, time-bound goal that everyone is working towards.

- Individual tasks are clearly defined and prioritized based on their impact in advancing the primary objective.

- Each task has clear boundaries around the time, resources, and role, and a clear flow of authorization.

Crucially, this flight plan doesn’t just provide external direction–it connects to the passions and inspirations of individuals within the group. When individuals can can see a clear connection from their day-to-day tasks all the way up to their own deepest sense of purpose, they tap into a wellspring of intrinsic motivation and energy.

In contrast, Fantasyland is the state a group falls into when there are breakdowns in the flight plan. Here, individuals become disconnected from the primary objective and fall under the unconscious influence of Shadow Dynamics. In Fantasyland, the group’s energy is dissipated by shadow goals that undermine progress and lead to entropy and dysfunction.

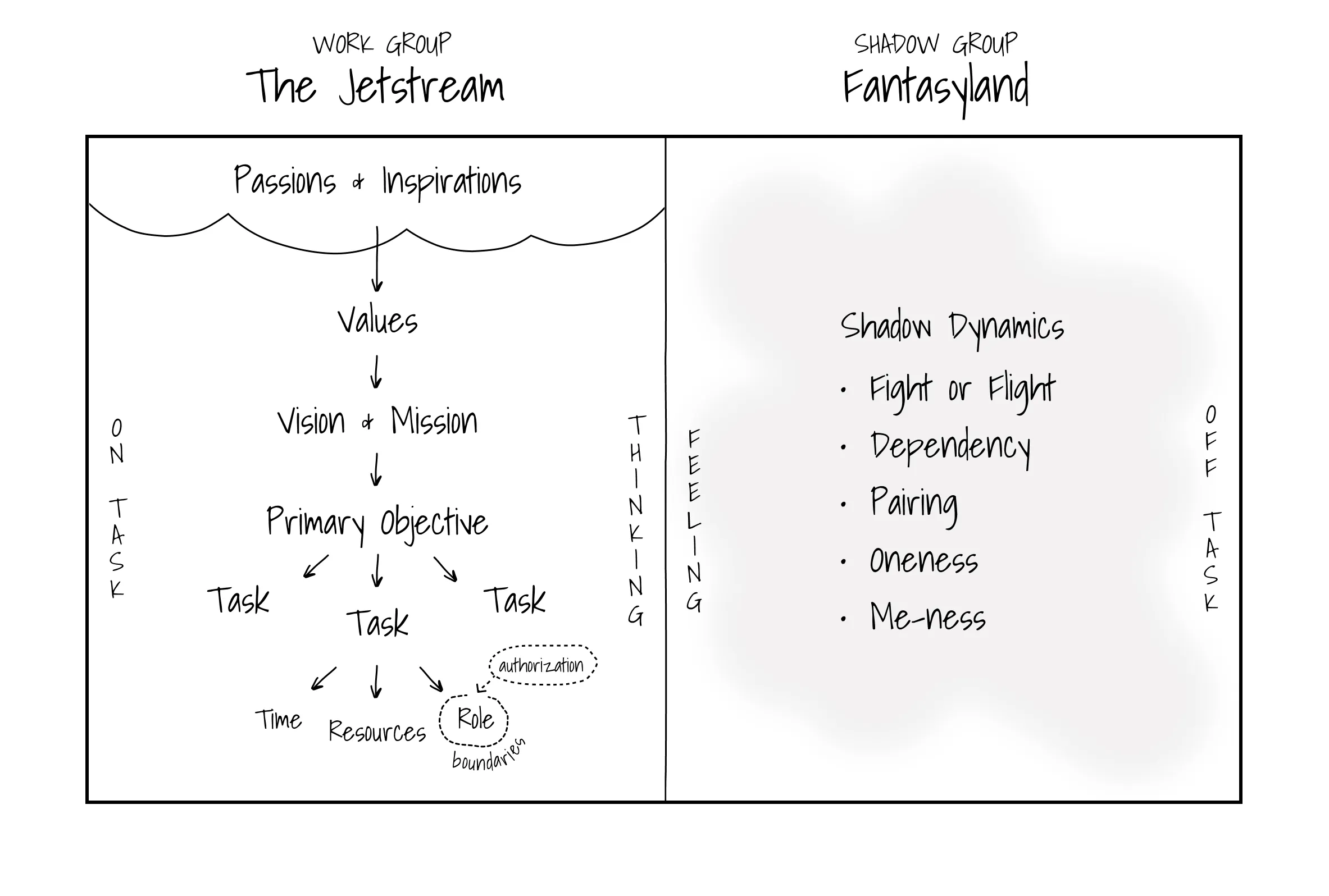

Work Group and Shadow Group

In any group, there are two parallel realities at play: the work group and the shadow group. The work group is the part of the group that is consciously focused on the task at hand, using rational thinking to solve problems and make decisions. This is the part of the group that is engaged in performing work that advances towards the primary objective.

The shadow group, on the other hand, is the part of the group that is concerned only with the psychological safety and survival of the group. Although this part of the group has become disconnected from the primary objective, it plays a role in maintaining the group’s near-term cohesion and well-being by attending to the feeling energy and emotional needs of the group.

Ultimately, if left-unaddressed, the shadow group becomes increasingly stuck in Fantasyland, undermining the group’s effectiveness and eroding the group’s ability to achieve its goals and fulfill its purpose.

In a healthy, productive group, thinking and feeling energy work together harmoniously. The group is able to stay focused on its goals while also attending to the emotional needs of the group. The work group and shadow group are integrated.

So, now we have a map of the territory. The question is, what do we do with this information? We’ll explore how to apply our framework in the next section.

Part Five: Orienting and Navigating

Think about a time when you were part of a group that was totally in sync, flying through The Jetstream. Maybe this was in a work context, perhaps it was when you were part of a sports team. What was that experience like?

Common descriptions of Jetstream experiences include:

- Flow, Focus, Productivity

- Energy, Motivation, Inspiration

- Creativity, Empowerment, Collaboration

- Trust, Safety, Ease

Now, think of a time when you were part of a group that struggled to achieve anything at all, that was lost in Fantasyland. How did that experience feel?

Common descriptions of Fantasyland experiences include:

- Stressful, Frustrating, Draining

- Slow, Stuck, Resistant

- Anxious, Fearful, Angry

- Confusing, Disorienting, Chaotic

It turns out that these feeling tones are useful information that we can use like a compass to orient ourselves and the group on the map.

In Group Flow, we challenge the notion that individuals are fundamentally separate from the groups they belong to. Instead, we view individuals in a group setting as inherently interconnected, constantly shaping and being shaped by the larger collective consciousness that emerges.

From this perspective, the boundary between individual and group is more porous and fluid than we typically assume. Each individual is not just a self-contained entity, but a node in a larger web of relationships and interactions that generate an emergent, shared reality.

We can think of the group as a complex, dynamic system, where the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of each individual member are both influencing and being influenced by the larger patterns and dynamics of the whole.

This means that whatever feeling tone is present for you is also present for the group and visa versa. When you’re feeling energized, inspired, creative, and safe that’s an indication that all or part of the group is on task. When you’re feeling stressed, anxious, frustrated, and angry, that’s an indication that all or part of the group is off task.

When we attune to our own embodied experience of the group’s feeling tone, we are tapping into the interface where the individual and collective meet. Our own feelings, sensations, and intuitions become a kind of sensor that picks up on the larger currents moving through the group.

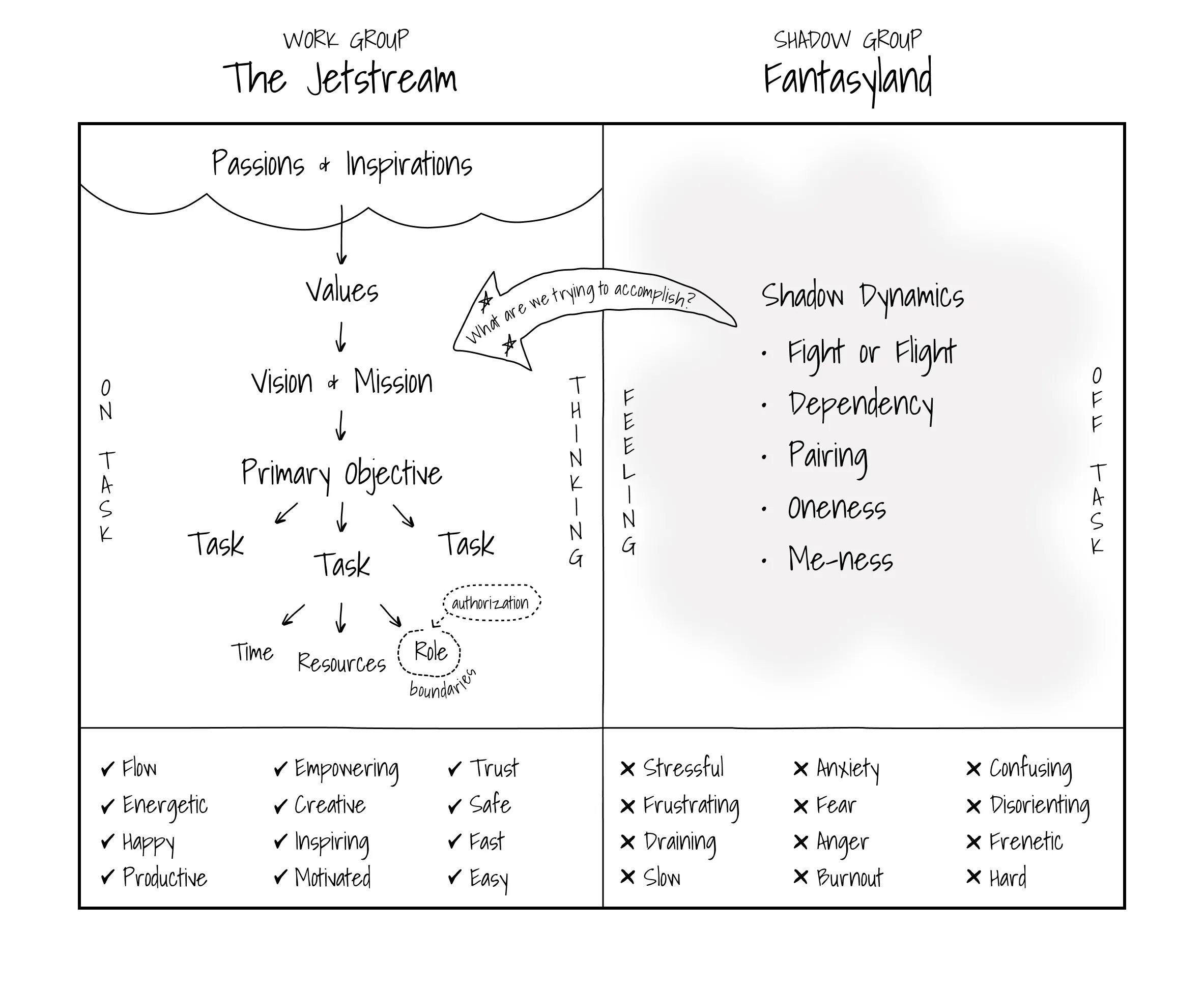

Think, Then Feel Your Way Back

Imagine for a moment that we’re in a meeting that has devolved into conflict. Tempers are flaring, voices are raised, and it feels like the walls are closing in. You might notice your heart racing, heat rising in your face and your vision narrowing to a tunnel as you’re consumed by feelings of anger, stress, and irritation. This feeling tone is a clear signal that the group, or part of it, has fallen off task.

The key thing to recognize in this moment is that it doesn’t actually matter who is off task or which Shadow Dynamic has taken hold. Whether it’s Dependency, Fight or Flight, Pairing, Oneness, or Me-ness at play, the path back to The Jetstream is always the same: consciously reconnect to the flight plan.

To do this, we use a process I call think, then feel your way back. The first step is to mentally disengage the group from the swirl of emotions and unconscious patterns by asking a simple question: “What are we trying to accomplish?” This question is like a cheat code to break the spell of Fantasyland and re-engage thinking energy, beginning the process of returning to task.

I used this phrase so often in my own company that it became a bit of a running joke, but it worked every time. Eventually, many other people began using it, creating a shared language and practice for getting back on track.

The next step is to consciously reconnect to the flight plan at whatever level you’re able to. Ideally, you can link back directly to the specific task at hand and resume productive work immediately. But sometimes, the influence of Shadow Dynamics is too strong for that direct connection.

In those cases, you need to zoom out to the level of the primary objective, reminding everyone of the overarching goal you’re working towards. If the chaos is so intense that even the primary objective feels out of reach, you work your way all the way up to the mission and vision–reminding the group why it exists in the first place.

I once found myself in an executive meeting at Tradesy where two members of our leadership team were seconds away from a physical fight. They were out of their chairs, in each others’ faces. One of them said to the other “If you don’t step back right now, I’m going to punch you.” The negative energy was so palpable, it felt like the oxygen was being sucked out of the room.

I stood up and said, in the calmest voice I could muster, “Hang on. What are we trying to accomplish here?”

We had come together to review and approve a new brand strategy, but in that moment, the current of aggression was so overwhelming that I couldn’t connect to that task, or even to our primary objective. So I went all the way up to our mission and vision.

”Our vision is to make commerce sustainable. In order to do that, we need to make fashion resale as safe, simple, and stylish as retail at scale.”

I felt ridiculous, waxing poetic about our mission statement while my colleagues were about to come to blows. But it worked. Within moments, the tension started to dissipate. Reconnecting to our higher purpose broke the spell of Fight or Flight, and we were able to agree on next steps to move forward. There was still some residual tension, but we were back on task, and no one had gotten hurt.

Once you’ve found an anchor point in the flight plan and re-engaged your thinking energy, the next step is to feel your way back to the Jetstream, allowing your emotions to catch up and come back into alignment. This part can take some time—you can’t just flip a switch and instantly return to The Jetstream after your detour in Fantasyland. The return trip takes some time even when you’re on course and have a GPS guiding you back.

Once you’re fully reconnected to the flight plan, you can start to diagnose what caused the breakdown in the first place. Was the task unclear? Do we have unresolved conflicts about priorities or resources? Do roles and responsibilities need to be clarified? From your renewed position of clarity you can make the necessary tweaks to your flight plan to prevent future mishaps.

The think-feel-adjust process might need to happen several times, at different levels of the flight plan, before the group is fully on course again. That’s normal—the key is to keep consciously reconnecting to what you’re trying to achieve together until it sticks.

What’s powerful about this approach is that anyone in the group can initiate it. You don’t need to be a leader to ask, “What are we trying to accomplish?” In fact, a key insight of Group Flow is that leaders are just as susceptible to getting pulled off task as anyone else. In order to prevent getting stuck in Fantasyland when we drift off course, we must empower all members of the group to keep each other on task.

By cultivating the skill of navigating with feeling tone and re-anchoring to the flight plan through the think-then-feel process, everyone in the group contributes to a powerful, distributed, self-organizing system for staying on task and redirecting energy towards the common goal. It’s like having a network of co-pilots, all working together to keep the plane flying smoothly in the Jetstream, making course corrections whenever necessary.

Task-Orientation and Feeling Tone

It’s important to note that not all unpleasant feelings indicate that the group is off task. In some cases, unpleasant emotions are a natural and even productive part of the creative process. For example, frustration when grappling with a challenging problem can provide the grit and determination needed to persist. Similarly, a sense of fear or anxiety in the face of an ambitious goal can actually sharpen focus and motivation.

The key is to learn to discern whether the feelings are task-oriented. Task-oriented unpleasant feelings, while uncomfortable, are ultimately in service of the work. They arise in direct response to the challenges inherent in pursuing the primary objective. shadow-oriented unpleasant feelings, on the other hand, are out of place in the context of the task at hand.

Positive feeling tones also don’t always mean the group is on track. Pleasant feelings can arise from Shadow Dynamics too: the euphoria of a Pairing or Oneness fantasy, the righteousness of indulging in Me-ness, the relief of falling into Dependency. These states might feel good in the moment, but they’re ultimately a form of avoidance or distraction from the real work of advancing our Primary Objective.

For example, a team might spend a meeting excitedly generating big picture ideas (Oneness) without stress-testing them or considering implementation details. Everyone leaves the meeting feeling inspired and aligned, but in reality no substantive progress was made. Or two team members might fall into an impassioned debate about a trivial matter (Pairing), derailing the agenda but giving them a feeling of being engaged, while the rest of the team is swept along in the powerful energy of the Pair.

Navigating this emotional landscape requires developing a nuanced and clear level of self-and-system awareness. We need to develop the capacity to both notice our feeling tone in the moment, and swiftly cross-referecne it with the task at hand. Is this feeling directly related to the work we’re doing, or is it a symptom of a Shadow Dynamic?

With practice, this becomes an automatic habit. We notice frustration arise and we quickly ask “Is this task-oriented frustration or a sign we’re off track?” We sense excitement in the room and check “Is this energy moving us toward our Primary Objective or is it a distraction?”

As we develop this skill, we begin to appreciate the deep, fractal complexity at play in any group. Each individual is navigating their own inner landscape of emotions and perceptions, while simultaneously being influenced by the currents of Shadow Dynamics at the collective level. It’s a delicate, intricate dance where the individual and the group are constantly shaping each other. Recognizing and embracing this complexity is a crucial part of working effectively in groups.

Ultimately, navigating with feeling tone and re-anchoring to the flight plan is a dynamic, ongoing process that requires the participation of the entire group. Due to the complex, ever-shifting nature of groups, there is no permanent solution to staying on task. It requires a continuous practice.

In the next section, we’ll dive deeper into what this looks like in action and explore practical tools for cultivating a culture of sustained group flow.

Part Six: The Practice

States of flow emerge naturally in the presence of a clear flight plan that channels group energy towards a common goal. In order to sustain these flow states, we must proactively and continually address and integrate unconscious Shadow Dynamics that divert energy into organizational entropy and ineffectiveness.

Working with Shadow Dynamics involves developing increased clarity about our own inner landscape. By learning to attune to our feeling tone and discern the task-orientation of our emotions, we gain a powerful compass for understanding whether the group is on task or off. Through think-then-feel, we develop our capacity to deftly steer the group back to flow when it falls off task. Over and over, we watch as energy drifts away, and we gently pull it back into focus.

Organizational Mindfulness

In this way, Group Flow can be understood as an organizational mindfulness practice. Just as individual mindfulness involves cultivating awareness of one’s inner experience and learning to skillfully direct attention, organizational mindfulness entails developing a collective awareness of inner experience in order to skillfully direct group energy.

Meditation teacher Shinzen Young defines mindfulness1 as a combination of three core attentional skills.

- Concentration The capacity to direct and sustain our attention towards a chosen object.

- Clarity The ability to vividly perceive and distinguish between the components of one’s sensory experience.

- Equanimity A state of non-resistance in which we’re able to be present with whatever is arising in our experience without pushing or pulling.

In group flow, we apply each of these core skills at the group level.

- Concentration We concentrate the energy of the group and channel it towards a primary objective. Through practices like think-then-feel, and by continually refining our flight plan, we strengthen our concentration power at the group level, allowing us to more effectively channel energy towards our goals.

- Clarity We develop clarity in order to discern feeling tone and untangle it from task orientation. We use this clarity to determine whether our energy is oriented towards the primary objective or pulled off task by Shadow Dynamics.

- Equanimity We develop equanimity with whatever arises in the group. Rather than judging, resisting or getting swept away by Shadow Dynamics, we recognize them as natural, inevitable features of group life. By cultivating equanimity, we can stay grounded as we skillfully address the causes of Shadow Dynamics rather than reacting to their manifestations.

With practice, the process of clearly perceiving our moment-to-moment feeling tone, and using the information we receive to make adjustments in order to refocus the group becomes almost automatic. The very presence of a feeling tone that is not task oriented kicks off the process of think then feel which guides us back to task.

But the real magic happens when this capacity is scaled to the collective level. When everyone in the group is engaged in this practice, we create a distributed network of awareness and course-correction. We catch each other when we stumble and guide each other home we when veer off course. In this way, the group develops a robust immune system against unproductive patterns, allowing it to avoid organizational entropy and channel its energy more effectively towards its primary objective at scale.

This requires a fundamental shift in how we understand our roles and responsibilities in group work. Staying on task is not just the domain of formal leaders, but a key part of everyone’s role. Followership becomes as critical a skill as leadership, and a core aspect of effective followership is helping to keep the leader aligned and accountable to the group’s mission.

In an ideal scenario, every individual has a deep, embodied understanding of the group’s primary objective and sees their role as actively contributing to that objective, not just completing assigned tasks. This empowers individuals to become self-authorizing, constantly assessing whether their current tasks are the best way to advance the collective goal and, if not, proactively escalating concerns and investigating alternatives.

Of course, this is a highly dynamic process. The group’s Flight Plan is always evolving, especially in fast-growing organizations. Tasks are constantly being completed or reprioritized, the primary objective changes from quarter to quarter, and even mission, vision, and values undergo periodic adjustments.

Systems, processes, and structures that served the group at one stage may quickly become outdated as the scale and complexity of the work changes. As such, we must continuously evaluate, tear down and rebuild our ways of working together. The map and practice of Group Flow provide a stable framework amidst this constant change, helping us navigate the challenges of growth and adaptation.

Practicing Group Flow effectively requires a high level of group emotional intelligence, but the rewards are well worth the effort. By developing our capacity for organizational mindfulness, we not only unlock greater productivity and effectiveness but also cultivate a deeper sense of individual fulfillment and connection.

Ultimately, this practice leads to a figure-ground shift in how we understand the nature of group work. We recognize that our internal work and our external work are not separate, but two sides of the same coin. By working on ourselves, we become more effective at working with others. And by developing the skills for effective group coordination, we simultaneously transform ourselves.

In this way, the transformation of the group and the transformation of the individuals within it reveal themselves to be one and the same process. As we shift the patterns and dynamics of the group, we are also evolving our own consciousness. And as we change ourselves, we become more effective at driving change within the groups and systems we are a part of.

This is the deeper invitation of Group Flow—to step into a new paradigm of group work that honors the fullness and complexity of our humanity while unleashing our collective creative potential. It is a journey of both inner and outer transformation, with the potential to reshape our organizations, our communities, and our world from the inside out.

Footnotes

-

If you’re interested in learning more about mindfulness, I highly recommend Shinzen Young’s book The Science Of Enlightenment, and the articles on his website, especially “What is Mindfulness”. If you’re interested in developing or deepening your meditation practice, a great starting point is an app called Brightmind, which was created by one of Shinzen’s students. ↩